Come for the course, stay for the community

I signed up for David Perell’s Write of Passage class expecting two things: (1) some tips and tricks for online writing and (2) weekly homework assignments that would hold me accountable to start producing content. In short, I was looking for a traditional school experience. So far, that’s been about 10% of the value of the course.

I was surprised to find that the other 90% hasn’t come directly from David—it has come from other members of the class. As we’ve engaged in small group video chats and commented on each other’s drafts and started interest groups on Circle, a Facebook-like tool designed for this very purpose, it’s become increasingly clear that the value of this course has more to do with the community than the classes. And that’s not because David is a bad teacher, it’s because he’s a great community builder.

This idea is in the same ballpark as one popularized by Chris Dixon about building social networks: come for the tool, stay for the network. Instagram started as a way to get cool filters for your photos and only later became the dominant network for people to share photos with each other. Cold-starting social networks is notoriously hard, so you often need to figure out how to provide single-player utility before you can turn it into a multi-player game.

Online courses and communities follow the same property. There seem to be two main lessons to learn here: if you want to build educational content, turn it into a community; if you want to build an online community, start with educational content.

Multi-player education

As schools of all shapes and sizes across the U.S. consider what Fall 2020 will look like in light of our inability to effectively control COVID-19, we have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to try new models of education. I am not an educator by trade, and I’ve seen my friends who are give eye-rolls every time someone says they have a shiny new educational model to save the day. I’m not here to promise a panacea or silver bullet, and I understand that what works for a highly motivated set of adults that paid thousands of dollars to proactively join an online course likely doesn’t apply to middle school kids living in poverty with disengaged parents. But, I also think professional educators should pause for a second and ask if they can learn anything from courses that people happily pay thousands of dollars for.

Unfortunately, we seem to have taken the worst aspects of in-person education and designed online education in the same image. Rows of desks facing a chalkboard have become isolated computer screens streaming pre-packaged videos. Online education is too often a lonely, uninspiring single-player utility that ends up feeling something like this:

It’s the default and it’s easy—everyone puts themselves on mute on a Zoom call and someone lectures. They might feign attempts at engagement (“…Anyone? Anyone? The…Hawley Smoot Tariff Act…”), but it’s no match for dozens of students sitting at their computers with their video turned off, one click away from dank memes and TikTok dances.

The irony of this is that the internet offers the tools for even better collaborative opportunities than in-person education. We think of education as a knowledge transfer product, but it’s actually a social product—and we’ve spent the last twenty years as a society mastering the art of online social communication. Now, online courses are blazing the trail by using tried-and-true internet tools to test new pedagogical methods that move all of education forward.

And while I’m probably massively oversimplifying how some of these lessons could be applied to more traditional educational environments, there’s a compelling emerging model of successful social education:

Cohorted classes. It’s pretty obvious that social education requires people interacting synchronously, but it’s equally tempting to think that one of the core advantages of online education is that it doesn’t require traditional “classes” of students completing the same work at the same time.

MOOCs (do people still call them MOOCs?), particularly the ones operated by universities, seem to make this fatal error. They record videos of professors’ lectures and post them online with a syllabus and some homework assignments and think they’ve made an “online class”. The problem is that an educational environment all but requires other people doing the same thing at the same time, people with which you can discuss and collaborate and learn from. You need to have peers that can hold you accountable to stick with it and a structured timeline that doesn’t allow you to put off the learning. These are the parts of traditional educational model worth preserving.

When I was signing up for Write of Passage, I couldn’t figure out why anyone would pay an extra thousand dollars to be able to join future cohorts after completing the class the first time, particularly since you can still access the course material either way. Now it’s pretty clear: the chance to meet and engage with the new cohorts of students, as well as the forcing function of mindset and accountability that the community provides is actually where most of the value comes from.

Asynchronous social spaces. While you need people to go through the educational experience across a defined period of weeks or months, you should still take as much advantage as possible of the opportunity to create virtual social spaces for people to interact. The aforementioned Circle is a great example of this.

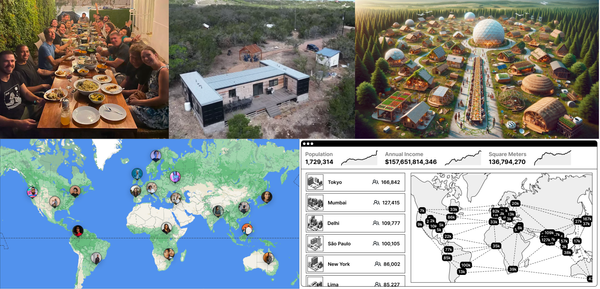

If you’re doing online education right, you’re attracting a diverse audience of learners from around the world. This will include people across a myriad of timezones, working professionals, parents with kid-driven schedules, and an unknowable set of other time constraints that require the flexibility for students to engage with the class whenever works for their lives.

But even in cases where you can more fully control and account for schedules (like, say, students paying $72,000 per year to go to virtual-Harvard), I still think there’s immense value in having asynchronous social network engagement. If you can create actual unmoderated conversation among students, you’ve found the holy grail. Of course, you have to be willing to tolerate (even encourage!) off-topic conversation for it to really work, and the fear of unmoderated discussion runs ironically deep in many academic institutions.

Schools have relied on tools like Moodle and Blackboard for online educational community engagement, but some combination of the tools and the methods of use remain embarrassingly under-powered, forced, and lacking anything that could truly be described as organic engagement. Asking students to write a 500-word post on Moodle is not creating engagement, it’s just changing the format for turning in an assignment.

Flipped classrooms. This one is almost too obvious to include, but given the number of educational institutions fumbling the ball as we approach the start of the new school year, it’s worth re-iterating: remote learning is the perfect environment for asynchronous lectures and live collaboration on project-based work, known as the flipped classroom model.

There is absolutely zero reason to ever make a large crowd of people all get on a video call at the same time to sit through a static lecture or presentation. It is a boring, horrid waste of people’s simultaneous attention.

Scaled interaction opportunities. Different students operate most effectively at different scales of social interaction, and you need to meet people where they are across the introvert-extrovert spectrum. Some will thrive in the conversational environment of regular breakout rooms of 2-4 people. Others will become class clowns or eagerly frequent contributors in the chat section of full-group live classes. Others may not say much (or even attend) the live sessions, but build their own niches of community within the gathering space of your social network.

Online classroom environments make this much easier than physical ones. Create a range of spaces for people to give each other detailed feedback, compare notes, debate ideas, and collaborate. If you favor only—for instance—in-class live discussions, you bias your classroom towards certain kinds of students and make everything feel stilted and painfully inauthentic. People will find their own way to get out of the experience what they put into it. Let them do this and then evaluate based on the product they create, not the process they used to get there.

Building an online community

In short, what I’m suggesting is that online learning works best when you build an online community. Beware that this isn’t easy—online communities are rare and wondrous specimens of the internet. I don’t mean social networks like Facebook, Instagram, or LinkedIn. I’m talking about communities with deep and distinct cultures: places like Hacker News, MetaFilter, and 4chan. Some sub-reddits would qualify. Loosely bounded entities like (sports, tech, black, finance, science)-twitter sit in an amorphous grey-area.

I know about these ecological niches of cyberspace because I spent most of middle and high school lurking on early iterations of global web-based communities (Digg, Hacker News, MetaFilter, Reddit). I’ve even tried to start my own online community. I was fresh out of college and idealistically confident about the future of online discourse. I envisioned a beautiful sci-fi fantasy that heavily borrowed from the Net of Ender’s Game: great writers and deep online debate driving socio-political decision-making. I was young, naive, and I certainly wasn’t expecting this.

But even if I’d tried to start an online community with slightly more modest ambitions and a more realistic understanding of people’s desires for online engagement, I would have failed. The online communities that seem to really stick are the ones built around an existing pool of content and its author. Both Reddit and Hacker News were seeded by the community of people who read Paul Graham essays. Digg grew (and imploded) around the figure of Kevin Rose. We should find this behavior of community building unsurprising, given that religions and cults have usually taken the same approach.

Were I to ever try to build an online community again, I wouldn’t launch the community until I already had one. I’d write, and gain followers, and then set up the infrastructure to enable them to communicate with each other. Bringing together people around a shared set of mental models may be the only way to get them to stick around and actually want to talk. In other words, I’d probably try to build something that looked a lot like Write of Passage.

Learning to internet

The irony of my love of online communities is that I was mostly a lurker, which sounds creepy but just means I read content and rarely posted. I feel some regret about this, but the general rule of thumb is that 90% of people in online communities lurk, only 10% engage at all, and 1% create almost all of the content. Like most people, I treated online communities like television—I was a consumer, passively scrolling and absorbing. I didn’t share my thoughts. I didn’t feed the trolls.

As a result, the greatest value I’ve gotten from Write of Passage has nothing to do with writing. It has been a full blossoming of realization that the internet should not be a passive medium, it should be approached as an opportunity to actively engage with the world.

In the past week, I have gotten feedback on my blog posts from half a dozen writers in the class, had a twitter debate about unit economics with a private equity guy, gotten live coding help from a programmer and photographer somewhere in the West Central Africa timezone, discussed trial law with a lawyer in Dallas, submitted bug reports via slack to the team running a piece of open-source software, talked about life with a doctor in Edinburgh, learned about acquiring small SaaS businesses from a guy in Phoenix…and on, and on.

In these conversations, particularly with my fellow Write of Passage course-mates, there is a kind hive mind. I can always find an area of mutual intellectual interest overlap, we can usually recommend a blog post to each other about the topic we’re discussing. It feels like I’m finally living in what Venkatesh Rao refers to as the Giant Social Computer in the Cloud.

The GSCC, or some similar manifestation of it, seems to be the future we are heading into. As traditional jobs turn into freelance internet gigs, learning how to plug your brain into this giant cultural cyborg may be as important to workers in the Information Age as preparing for a factory setting was to workers of the Industrial Age.

As we approach school returning in the fall, figuring out how to educate kids is one of the biggest and most important questions society faces. And if actively engaging, creating, debating, networking, and marketing yourself are keys to 21st century success, then schools have an incredible opportunity to change the educational model to fit this mold.