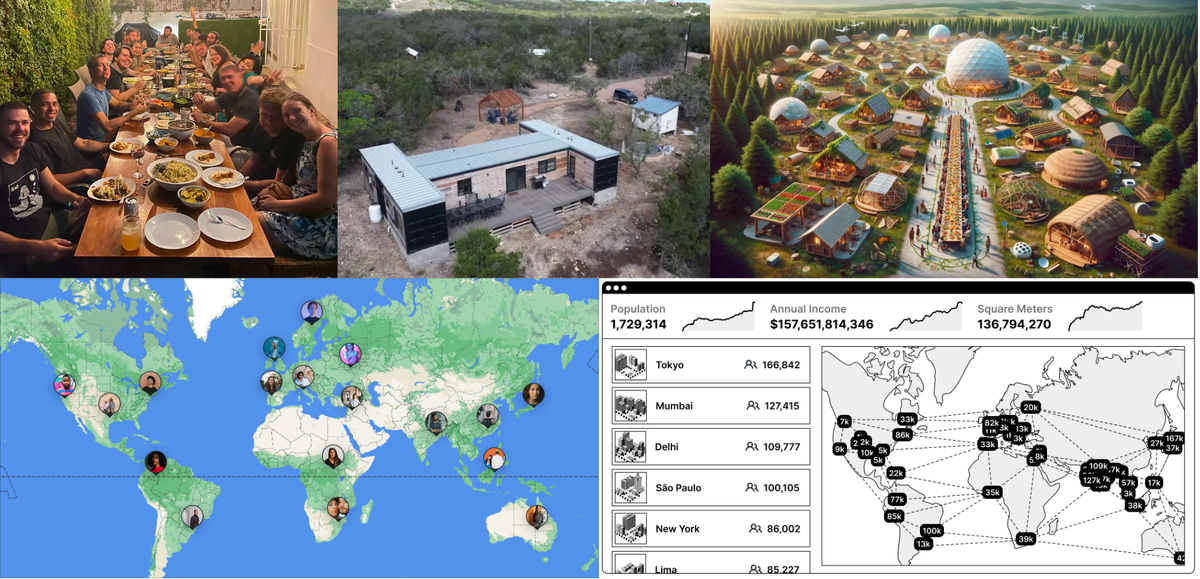

Supper, place, village, city, state

There's a basic playbook for building startup societies. It goes: supper, place, village, city, state. You start with dinner, and coordinate your way to something bigger. Over time, you can grow large structures of human coordination—maybe even new types of cities or states.

Traditional suppers, places, villages, cities, and states are built around a geographical location. They share cultures, economies, and governance structures (however formal or informal), but most of all they share the same physical place. This sense of place ultimately defines the community—if you moved every resident of Austin to rural Idaho, it would be hard to say that it was the same city.

Network suppers, spaces, villages, cities, and states also share physical space, but the specific locations where they gather are secondary to the culture they gather around. They are communities drawn from the internet to colocate IRL. A sense of place is still deeply important to network communities, but if they all relocated to a new place, the core would remain intact. This ability to exit as a last resort creates flexibility, freedom, and resilience for local communities and the people who live in them.

Network societies should always start small and grow over time, because they are complex systems that follow Gall's law:

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over with a working simple system.

As you grow from supper to state, it's important to remember that while each stage is bigger than the last, that doesn't make it better. In many ways, dinner parties are much more fun and personally useful to people's day-to-day lives than states. The secret sauce of communities is in small scales. So you should discerningly choose where on the spectrum you want to go to, and stop there.

Supper

If you want to build a network state, start with network supper. Or, in the infamous words of Richard Bartlett:

guy who has never hosted a dinner party: I should start a network state

— Richard D. Bartlett (@RichDecibels) December 31, 2022

Richard backs this pithy phrasing up with a strong framework he calls microsolidarity. The basic idea is that humans glom together into a range of small group sizes, from partnership to crew to congregation to crowd. Each agglomeration of people is built out of a fractal pattern of smaller scale structures:

He identifies the crew (3-6 people) as the core unit that changes the world—and it is defined by its ability to fit around a dinner table:

A crew is a very small group. The numbers are not precise, but I think about 3, 4, 5 or 6 people. It’s a group that can fit around a dinner table and have one shared conversation.

So if you're hosting your first dinner party, don't worry that not enough people are going to show up — worry that too many people might! We've been hosting dinner parties around the world over the past few months at Cabin (come join us!). Whether 5 people or 50 people attend, these small gatherings allow people to form tight knit crews in their local area.

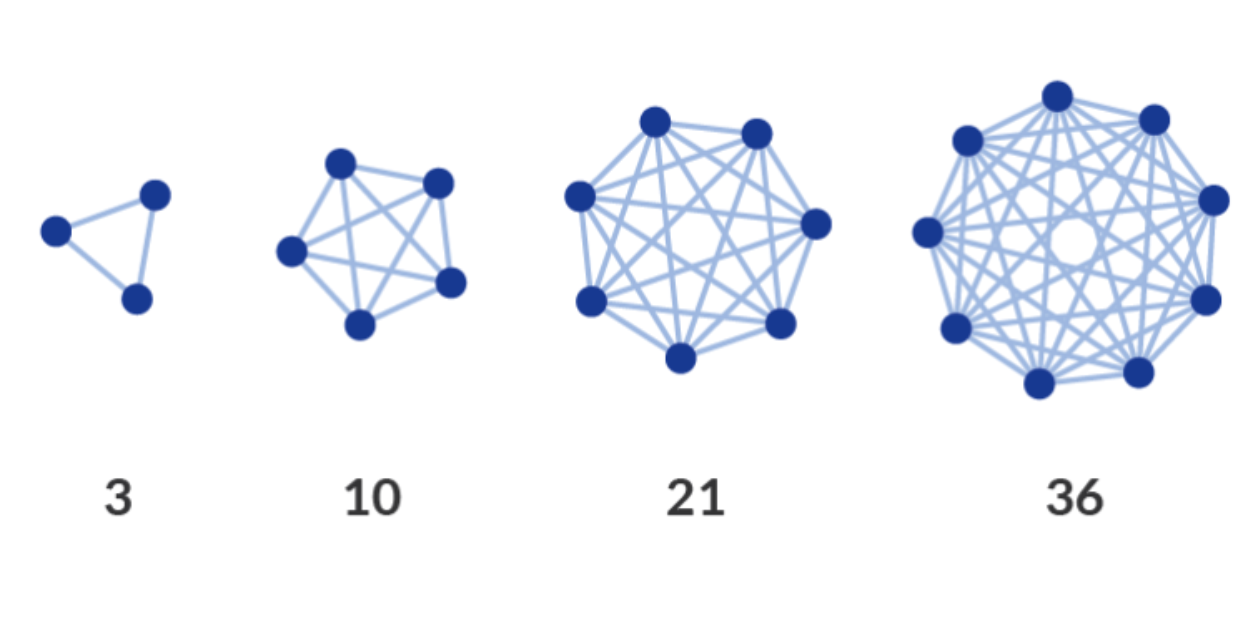

Finding the right crew is crucial, because it's the most effective unit of human collaborative creation. Successful groups tend to be small and purposeful. More people often does not result in better outcomes, because coordination costs increase geometrically. This coordination cost is the flip side to Metcalfe’s Law — 3 people have 3 total relationships to manage, while 9 people have 36:

When everyone has a relationship to everyone else in the group, it's much easier to self-govern—you can usually do it informally without even calling it governance. And this type of small scale governance sets the foundation for larger scale coordination. If you can't decide how to cook a meal and clean up the dishes together, you probably shouldn't try to develop more complicated governance systems.

Once you've got the fire started, you can start to grow a larger community that doesn't require high context relationships between between every member simultaneously. The initial flame of the founding crew can serve as a vibe signal that will attract the right people from their collective networks.

Place

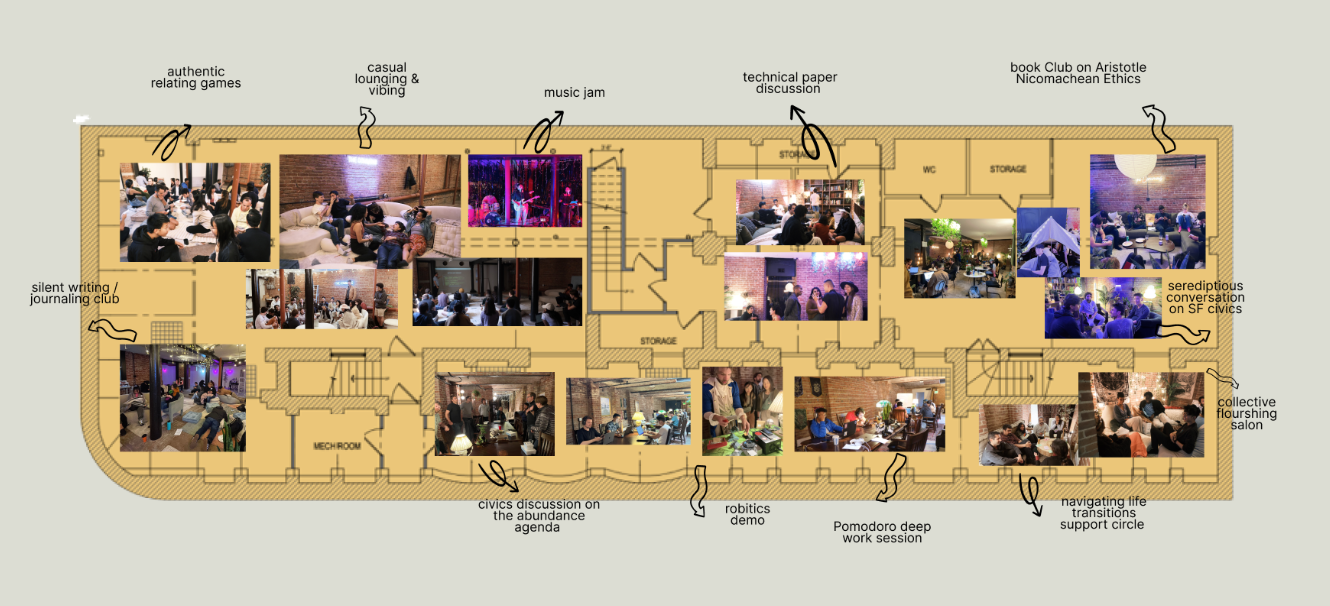

Once you have a rotating cast of 15-50 people coming by your place regularly, you can start to tackle bigger coordination challenges. If you can convince 20 of them to chip in some money, you can get yourselves a shared place. A community clubhouse. Somewhere to meet up, hang out, break bread, make things, and learn from each other.

This is a major unlock for community building, because it creates a shared container for co-creation, a common ground between members, and a default place to go to bump into other members of the community. It lowers the friction to hosting events and hanging out with nearby friends. It provides a place for visitors to stay, which lowers the friction for new people moving nearby. And, it demonstrates a capacity for collective action that can be expanded upon.

Third places (not home or work) were at the center of American social life for much of the 20th century, driven by organizations like Rotary Clubs, American Legions, Boy Scouts, churches, and bowling leagues. The book Bowling Alone shows membership and participation in social and civic organizations swelled in the middle of the twentieth century and then went into steep decline starting in the mid-late 1960s.

Luckily, we're seeing the growth of new third places that can serve as the seed for regrowing dense communities. The Commons has built a thriving community third space at the center of a dense neighborhood of coliving houses in SF. Others like Groundfloor and Maxwell Social are growing from hundreds to thousands of subscribers with similar models.

But, you can and should start much smaller. If you get 20 people to commit to a $150/mo membership, you have $3000 / month. That's enough for a nice 2+ bedroom apartment or small house in most places. Cabin is exploring the role it can play in creating these sorts of micro third places for local communities. One of the best things we can do to seed hundreds of network villages is to launch hundreds of network third places.

Village

Network villages form when a network of friends start living together. Villages cover a few orders of magnitude in size, from around 20 people to perhaps 2000.

When people dream of an ideal future for themselves and their families, it often involves a group of friends starting a little village together. Big Religion has tried to brand these projects as communes or cults, which has put the wrong perception into people's heads. But, for the most part, people just want to live near friends in a place like this:

There are two types of network villages: urban and greenfield. Urban network villages are a social layer built on top of existing urban infrastructure. Greenfield network villages are built from the ground up. People often want to jump straight to building a greenfield solarpunk utopia, and there's a long historical tradition of this. But it's much easier to start with an urban network village and then relocate to more rural settings when you've built a critical mass of community.

Urban network villages are communities that intentionally live near each other to create new neighborhoods on top of existing urban environments. They usually have a third place at the center of them and are surrounded by thriving coliving houses, regular events, and educational opportunities. There are several good models of urban network villages that already exist. Radish in Oakland is built around a multi-house compound. The Neighborhood has grown around a third place, The Commons. Fractal exists within a single large apartment building in Brooklyn.

Greenfield network villages are built from the ground up in undeveloped areas. This is an extremely difficult thing to do from scratch. The first challenge is building the basic infrastructure—water, septic, energy, housing, transportation, internet, etc—that you can take for granted in an existing city. This tech stack has only become feasible for small groups in the past decade as solar panels have gotten cheap, satellite internet has become ubiquitous, and prefab construction techniques have improved.

Even after you have the basic infra in place, most people want at minimum a grocery store, coffee shop, bar, restaurant, etc within a short distance of where they live. And even if you can build all of these amenities, you still face the cold start problem of getting groups of people to move somewhere nobody lives yet.

Despite the challenges, greenfield developments are still worthwhile because they have clear advantages. Building from the ground up creates deep resilience. The best store of value is a local community—especially if it has the capacity for producing local energy, water, food, and housing. Greenfield developments can be custom built to the needs of the community over time, can be developed quickly without onerous building regulations, and can produce housing at dramatically lower costs than in cities. Finally, they can give people the best of both worlds: city-level social density with rural access to nature.

Culdesac is the furthest along so far, having built the first dozen buildings of their car-free village for a network of 1,000 modern urbanism enthusiasts. Neighborhood Zero, Cabin's founding village, is building a solarpunk oasis on 50 acres in the Texas Hill Country currently open to hundreds of Cabin Citizens. Morazan, which aspires to grow into a city, is currently a greenfield network village operating as a ZEDE in Honduras. They already provide low cost, safe housing options to hundreds of local Honduran families and have plans to build more.

City

A network city is a set of villages with an overlapping culture, economy, and governance structure. This is what we aspire to build at Cabin: a network of modern villages for families. If a village is 20 to 2,000 people and a city is 2,000 to 20,000,000, a network city is probably made up of 10s to 1,000s of villages.

Network cities create a flow of people and ideas between villages that leads to a growing shared culture and economy. They also grow resilience and freedom for individuals and groups. Having many villages to choose from means you can find a perfect social niche and always have other options if you decide you don't like the local governance, vibes, or weather. While exit is generally a last resort, the ability to move as an individual or community creates resilience against ecosystem, demographic, political, or social collapse.

Economies grow via a process Jane Jacobs calls import replacement in her book, The Economy of Cities. Network city economies grow similarly, with a few additional advantages. First, they can import remote work salaries into new job markets, eroding the monopoly on high-value job agglomeration held by the biggest cities and solving the cold start problem for new developments. Second, they can grow rapidly with reduced transaction costs across trusted digital networks. Third, they can use new financial infrastructure provided by blockchains to increase transparency and composability.

Blockchains play a less appreciated but even more important in network city governance. While local villages can generally be governed using simpler methods like do-ocracy, blockchains provide a layer of transparency and anti-capture that makes it possible for villages across the world to trustfully collaborate, even if they never meet in person.

This is important because major new ways of living have consistently evolved from villages, towns, and city states into federated networks with loose shared governance. The greatest source of human flourishing in history may come from using coordination technologies to build federated network cities:

State

Network states were theorized by Balaji Srinivasan in his eponymous book, The Network State. Balaji wrote a helpfully precise definition in the book:

A network state is a highly aligned online community with a capacity for collective action that crowdfunds territory around the world and eventually gains diplomatic recognition from pre-existing states.

As you can see from this definition, the key thing that separates network states from everything else I've talked about is their desire to gain diplomatic recognition from pre-existing states. So if you don't care about international diplomatic recognition, you can stop right here—what you want to build is somewhere else on the list.

And if you want to read on, ask yourself why you need diplomatic recognition in the first place. Getting diplomatic recognition from existing states is a huge task that takes years of effort and isn't necessary in order to do most of what you might want to do.

For a greenfield village development (most people's ultimate goal) there are still many states where unincorporated land provides the owner with a wide range of development rights. If what you want is the ability to build things without having to file a bunch of paperwork and follow some municipality's zoning rules, you can already do that in many places. No permission necessary! In fact, most states in the US have provisions for starting your own municipality, which often requires something like 500-5000 people vote on it. Get 500 people to move somewhere and you're well on your way to writing your own zoning laws.

If you want to change more than zoning, consider building on top of an existing special economic zone. Prospera, a ZEDE in Honduras, has a fascinating civil code that allows you to bring your own regulatory environment from any jurisdiction in the world or create your own new one from scratch. I think of network cities as L2s built on top of existing states and special economic zones. If you want fundamental security guarantees, build an L1 blockchain or state. If you're a community builder (and why would you go to the hassle of throwing dinner parties and managing a third place if you weren't?), you can build an L2 and leave the 51 percent attack risk vectors, monopoly on violence, and international arbitration agreements to someone else.

So, given the hassle involved and the alternatives available, who should build a network state? People who really want to do something that's not legal or extremely regulatory burdensome where they already are. Balaji calls this a moral innovation.

One real world example is Vitalia, a startup society building the City of Life. They view immortality as a moral imperative, so it makes sense for them to locate in a jurisdiction where experimental life extension gene therapies can be used before they are approved by the FDA. But even in this case, Vitalia doesn't necessarily need their own network state. Vitalia's pop-up city was hosted at Prospera, which has the legal authority to allow companies to offer non FDA approved treatments.

If the United States keeps cracking down with aggressive legal actions against crypto, you can bet it will spawn crypto network states. I believe that major blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum already qualify as network states. Ethereum is a state machine managed by a network, a blockchain leviathan that can’t be controlled by existing nation states, and a legible record of identity and money. Blockchains don't need to ask existing states for diplomatic recognition, they just earn it.

Blockchains earning diplomatic recognition organically points to a world where the concept of sovereignty gets squishier and more complicated. Honduran ZEDEs do not have diplomatic recognition as states, but they have legal recognition from a state that lets them write their own civil code. American states are not internationally recognized as states, but they were originally framed with much more sovereignty than they have now. If you mint a bitcoin in the Catawba Digital Economic Zone and sell it to El Salvador, to what extent was the server in South Carolina under US territorial sovereignty?

I have no idea, but my point is that the definition of "diplomatic recognition from existing states" is a moving target that will continue to evolve. It's looking increasingly likely that existing institutions continue to fracture, new special economic zones emerge, and population declines change the calculus of current sovereigns. If you have an idea of how to rebuild new international institutions, maybe you should start a network state. But even then, you'll have to begin with something that looks like a dinner party.

Interested in starting your own supper club, third place, or network village? Head on over to Cabin's forum and start a new topic to introduce yourself and the place where you want to build community. We'll help you get started on your journey.