From last-mile to last-minute logistics

The great challenge of logistics has historically been the last-mile: in a fractal expansion of road networks, how do you traverse the last bit of distance to every home? It is an under-rated marvel of modern civilization that this challenge has been largely and quietly accomplished in developed countries like the United States (and is slowly but surely being solved even in remote corners of the world).

My parents live on a ranch in Texas, a two-hour drive from the nearest metropolis and then miles down a winding dirt road covered in cactus and cow poop. After crossing seven cattle grids, three creek beds, and a lot of desolate land, you arrive at their front gate to find a large mailbox designed to receive packages. The rest of the family rolled our eyes when my dad installed the mailbox a few years ago, but Amazon recently started delivering right to the front gate (!)

It takes a literal army of post office workers and Amazon delivery drivers to pull this off, a behemoth of coordination and corporate will. But the savvy American consumer, aided by the unyielding mechanics of modern capitalism, always wants more stuff faster and cheaper. People have increasingly decided they don’t just want things brought right to their house. They want those things right now. Last-mile logistics is becoming last-minute logistics, and solving for speed requires a very different approach than solving for geographic coverage.

Traveling Salesmen and $0.55 stamps

To get a mental image of the challenge of the original last-mile problem, imagine if Amazon somewhat arbitrarily covered the United States in circles with a 1 mile radius. If every home was covered by one of these circles, and there was a delivery drop-off point at the center of each circle, everyone would be within a mile of a place where they could pick up deliveries. There would be, give-or-take, a million of these circles across the USA (3.8 million mi² / 3.14 mi²).

A million delivery drop-off locations is nothing to sneeze at. But there are 130 million households in the US, so taking this approach instead of delivering to each household individually would make Amazon’s delivery routes about 100x easier (I am oversimplifying a bit here, but the general idea holds). That last mile is a real pain, but for better or worse, people have come to expect things delivered not just to their neighborhood, but to their house.

If you have enough volume of packages (and people aren’t particularly picky about exactly when the stuff arrives), you can load all the stuff in a truck, pretend you are a Traveling Salesman, and drive around in a defined route that ends up looking something like this:

The density of your delivery locations is important, because you can subsidize the fixed costs of driving all over the place across more deliveries. Think of your friendly neighborhood mail-person. Because she delivers to essentially every house, the “cost” of adding your house to her route is small—she already has to drive past your house as she goes from your right-side neighbor to your left-side neighbor.

In other words, there is a tremendous economy of scale to route-based deliveries. Once you reach critical mass of delivery density, you’ve taken the extremely challenging last-mile problem and turned it into a last-foot problem (the distance from your curb to your mailbox). And there’s probably something else being delivered to your mailbox at the same time, so the incremental cost of dropping in one more letter is negligible. This is why mailing a letter across the country and having it hand-delivered to someone’s house costs the shockingly low price of $0.55 (despite common misconception, the Postal Service receives no tax dollars for operating expenses and relies on the sale of postage, products and services to fund its operations).

How speed beats scale

Very few organizations have reached the kind of density that allows you to solve the last-mile problem with route-based deliveries: The Post Office. UPS. FedEx. Amazon. Even within this sparse list, everyone is ultimately relying on the Post Office’s last-mile infrastructure (though Amazon has taken the leap into building out their own end-to-end last-mile systems, at the cost of billions of dollars per quarter).

If you’re an AMZN bull (and I am, for the record) their logistics network is one their greatest moats. But there’s a problem with this moat: on the ever-accelerating hedonic treadmill of consumer preferences, people (ironically aided by Amazon’s relentless focus on reducing delivery times and killing delivery fees) have increasingly decided they want their stuff to show up immediately.

This need for speed has changed the name of the game: last-mile logistics has become last-minute logistics. When people want things in the next hour or two, you don’t have the luxury of giant, highly efficient, pre-planned traditional traveling salesman routes. If people want stuff now, you have to solve a much harder problem and you have to solve it much faster.

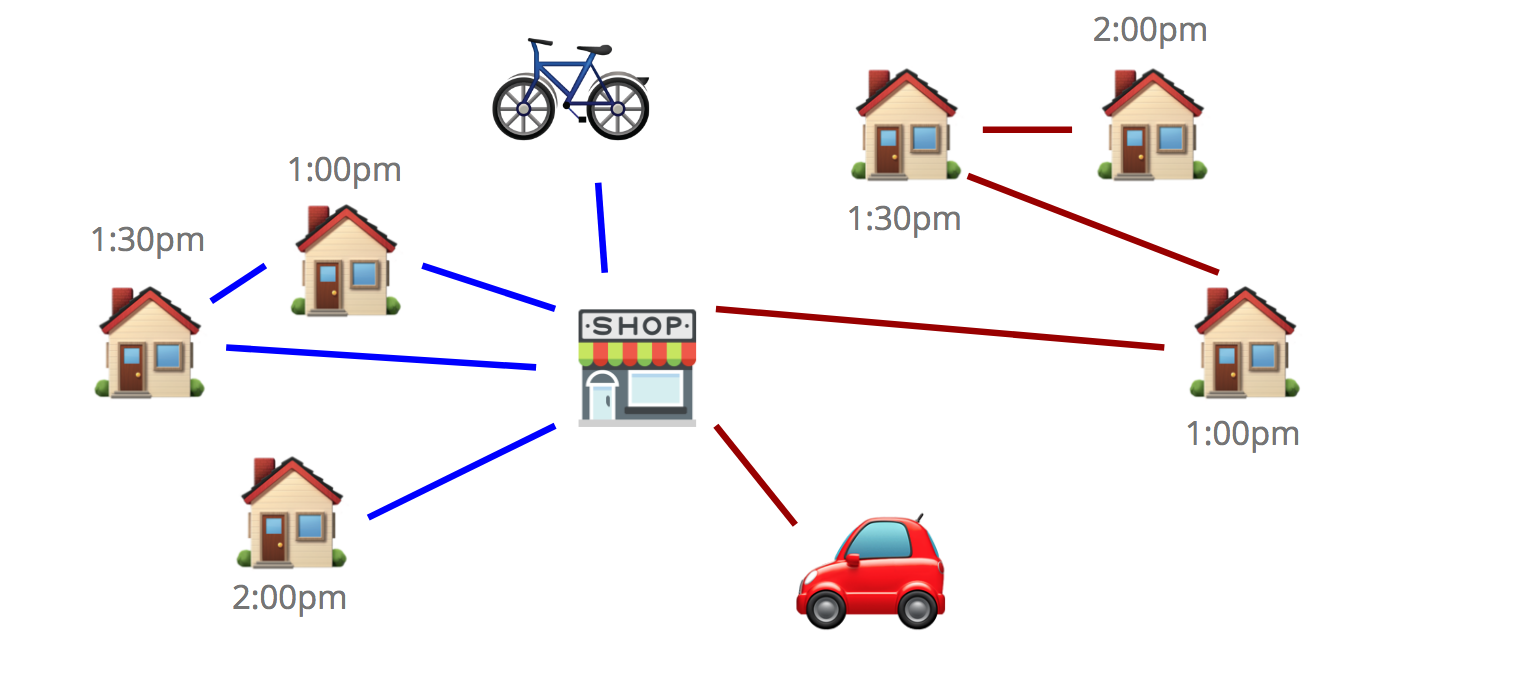

The already notoriously hard and computationally expensive Traveling Salesman Problem of last-mile logistics is a walk in the park compared to the mind-boggling Stochastic Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows and Multiple Trips. The SCVRPTWMT (if you want an easy-to-remember shorthand) is how we solve last-minute logistics problems at Instacart, and it looks something like this:

In plain english, the problem is essentially: how do you get stuff to people by a certain time in the very near future while the rest of the world is constantly changing around you?

Solving this problem is not just computationally harder than solving more traditional last-mile logistics problems, it also requires a fundamentally different approach. Top-down, infrastructure-heavy, meticulously-planned logistics becomes brittle and unadaptable to the needs of last-minute delivery.

Why Webvan imploded and AmazonFresh withered

Webvan was the epitome of Dot Com mania. It went public in 1999 at a valuation of $4.8 billion on cumulative revenue of $395,000 and cumulative net losses of more than $50 million. In a mere 18 months, the company burned over $800 million in cash before going bankrupt in a spectacular display of excess that looked something like this:

As has been throughly diagnosed in business school cases ever since, Webvan committed suicide via massively over-expanded logistics infrastructure. They bought parking lots full of refrigerated delivery trucks and filled massive warehouses with a billion dollars worth of top-of-the-line technology:

Jeff Bezos, who presumably had immense piles of cash lying around and not enough ways to light it on fire, decided to hire the same people who ran Webvan and run the same playbook—rebranded as AmazonFresh—with unsurprisingly similar results. Why did both of these companies make the same mistakes?

Because they were attempting to follow the tried-and-true playbook of last-mile logistics:

- Invest heavily in top-down infrastructure

- Forecast, plan, and optimize routes

- Gain massive efficiency at massive scale

- ???

- Profit

While this playbook has historically worked well for last-mile logistics (as we saw with the Post Office and Amazon’s traditional delivery business), it fails when you need to get people things quickly, either due to consumer preferences or the need to keep items temperature-stable (as with grocery and restaurant delivery). Your impressive infrastructure and meticulous plans go from being an asset to a liability.

Limiting liabilities with last-minute logistics

If you want to solve problems like the Stochastic Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows and Multiple Trips, you need to make some adjustments to the logistics playbook by optimizing for real-time flexibility and adaptability over maximum theoretical efficiency. The first rule of last-mile logistics is that meticulous planning is essential. The first rule of last-minute logistics is that meticulous planning is impossible.

The first problem with planning is that the world is constantly changing. The USPS has built complex planning algorithms that run on very large and fast computers, and it still takes them most of a day to create their route plans. The problem is that by the time they calculate the routes, more packages have come into their system, and the whole thing is woefully outdated. A delayed map is increasingly divorced from the territory.

The second problem is that forecasting is hard, and the further out into the future you go, the harder it gets. Knowing what will happen two weeks from now is much harder than knowing what will happen two days from now, which is much harder than knowing what will happen two hours from now. The magic of last-minute logistics is using real-time signals to focus on accurate predictions of the near-term over precise predictions of the longer-term.

The magic of last-minute logistics is using real-time signals to focus on accurate predictions of the near-term over precise predictions of the longer-term.

This doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t predict demand patterns for two weeks from now. It just means you shouldn’t trust or rely on those predictions too much, and you should be able to quickly adapt in real-time to meet the needs that actually arise. Don’t pre-design complicated optimal routes, just try to do the best you can with the options available in the moment.

Relying on real-time signals allows you to have a more accurate picture of the evolving stochastic state of the world, but it also requires you to be able to use those signals effectively. You need to have adaptive operational structures and flexible infrastructure. Instacart has succeeded where Webvan and AmazonFresh failed by building a low-friction bottom-up marketplace instead of a top-down centrally-planned economy. Instacart’s constantly evolving delivery routes, on-demand shoppers, and real-time incentives give it the flexibility to meet customer demand precisely when it occurs.

This ephemeral infrastructure is not only better suited to last-minute logistics, it also is much easier to bootstrap. Instead of needing to amortize billions of dollars worth of infrastructure across extremely high density deliveries, you can start small and local. And if you do this well, you can use your lightweight infrastructure to outmaneuver the trillion-dollar behemoth of Amazon’s logistics powerhouse, like guerilla warriors outflanking traditional armies.